THIS IS A DRAFT

Reflecting on the significance of software architecture is paramount in today’s dynamic landscape. We have transitioned from adhering strictly to substantial upfront design to recognizing that software architecture cannot be entirely predefined; rather, it necessitates an evolutionary approach, adapting and maturing in tandem with time and circumstances. While we have borrowed the concept of architecture from the realm of civil engineering, there exists a fundamental distinction between the two disciplines.

When we discuss software architecture and the role of software architects, the typical image that comes to mind is that of complex diagrams, filled with boxes and arrows, pointing in every conceivable direction. This visualization is a ubiquitous sight across organizations. However, it is crucial to question the efficacy of such depictions in truly capturing the essence of software architecture.

In my experience, I have often encountered these architecture diagrams—whether they be on wikis, shared folders, documents, or even mind maps—sprawled across the company’s knowledge base. There are even specialized tools designed specifically for crafting these diagrams. While these diagrams may appear logically sound and coherent at the surface level, in practical application, they often fall short, resulting in “half-baked” solutions and “incomplete implementations” that deviate significantly from their initial intent. Often when these architecture depictions and diagrams don’t get into action in the way they are inked, the question becomes pretty apparent, what is this software architecture? And does it matter?

In civil architecture, once a design has been finalized and construction initiated, there is little room for structural alterations or deviations from the original blueprint. The integrity of the structure hinges on strict adherence to the predetermined design specifications.

While there may be flexibility concerning the construction of additional floors or independent structures within the skyscraper, deviation from the established architectural plan is not a viable option. On the other hand, this is what building software excels at.

In the endeavor to define and create a robust software architecture, it is imperative to acknowledge the inherently flexible nature of software engineering. Although deviating from an initial design can present challenges, it remains a feasible option within the realm of software development. By its very definition, architecture serves as a foundational blueprint, delineating key considerations and charting a course for their practical implementation during the construction of the final product. Given that software development is characterized by incremental progression, as opposed to a comprehensive upfront design, it logically follows that the creation of extensive presentation materials and intricate architecture diagrams is an unnecessary and potentially counterproductive exercise. This perspective is aligned with the principles of agile methodology, which emphasizes the importance of maintaining flexibility and adaptability as the system evolves and expands over time.

Architecture must consider the malleable nature of software, Agile thought process promotes ‘agility’ – a way to adapt things as we go on building various parts of the system.

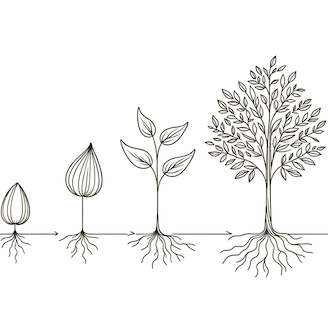

The process does not look like taking a blueprint and converting that to building, but rather looks like growing a tree from sapling, much like we grow our teams and orgs. The way we adopt and change team building decisions based on people. Because we really do not know exactly who will join in the future, but we do know what where they should head in terms of direction.

Melvin Conway depicted this, when he talked about “Conway’s Law”

“Any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization’s communication structure.”

We have experienced this in multiple cases where teams that kind of mimic software design or vice versa, have a much better shot at consistent and reliable software delivery, for example, consider the following table:

| Software Architecture | Organisation Architecture |

|---|---|

| Monolith | Mostly 1 team |

| Sync Microservices | Per service team, shared services owned by all teams, 1 - 10 teams, more messaging |

| Async Microservices + Infrastructure | 10 - 100 teams, SRE Islands, More communication over emails, documentation becomes very important for shared context |

| Distributed | 100+ teams |

This makes it a clear case for software architecture and modularity to evolve with organisation, and not upfront. The recurring pattern observed across numerous organizations highlights the pivotal nature of architecture evolution in tandem with organizational and software growth. The transition from a monolithic architecture to a microservices-oriented structure exemplifies the significant shifts that occur during this maturation process. Techniques such as implementing database caches, instituting asynchronous delayed jobs, orchestrating separate scheduling for cron jobs, and bifurcating database reads and writes are adopted to accommodate the escalating complexity and intricacy of the system.

It is imperative to note that as software architecture evolves, the delivery of software can exhibit a tendency towards deceleration, a topic that merits its own in-depth exploration.

Returning to the matter of software architecture, the continuous and dynamic growth of software can be likened to the process of a sapling maturing into a fully-grown tree. This analogy prompts the question: What strategic decisions and considerations must be employed to ensure the thriving growth and vitality of the software, rather than its demise?

We should think about software growth, it is similar to the way trees grow out of sapling… What kind of decisions do we make so that it does not die, but grows nicely?

Just as gardeners must have a common understanding of the essential tasks such as watering, shading, and fertilizing to ensure the healthy growth of a tree, software teams must align on fundamental practices within their architecture. This includes having a shared comprehension of the tech stack, agreeing upon a consistent programming style, and maintaining a unified approach to problem-solving. Just as the gardener’s practices contribute to the tree’s flourishing, these aligned processes in software architecture are crucial to the success and efficiency of a project, ensuring that each team member is contributing effectively towards a common goal.

The most important decisions to help grow a tree among gardeners is to have a shared understanding of when we water, when do we move it to shade, when to put fertiliser, how much moisture we need to maintain?

And if we don’t have a common understanding about what to do when in someone else’s absence, not only it creates a truck factor but also creates a possibility of death for that sapling. Software architecture is similar, it does not have to big, but mostly this is early days important decisions that everyone can take if they agree upon what to do.

Martin Fowler discussed this in his keynote in OSCON 2015, I remember once discussing many kind of MVC patterns with him during his one of his visits to India, and he said

as long as Model, View and Controller are doing what they are doing, it does not matter whether you render model in backend and send it to the browser, or bring data, and render it using JavaScript,

So it’s pretty clear that we let Architecture to evolve, but must have “common understanding” of how components interact. If we think from this lens, and if we start writing down our principles on how we will decide on important decisions, things will scale.

Going back to the tree example, you might have to cut off branches to keep the tree in shape, same way, you might have to discard or reimplement some part of software without getting worried about sunk cost fallacy. Another example can be to provide support by a small stick to strengthen the tree, and allow growth. Same way we can think about a lot of software as a service products (SaaS) in the early days, to provide strength in the early days and not worry about building it out.

If we think about these decisions – these are one way decisions Jeff Bezos has some views on this as well

These decisions aren’t easily replaceable, eg, hiring people is usually one way decision, working on your tech strategy becomes super important because it’s again mostly consists off one way decisions, those of course can be change, but change is costly. For example, choosing tech stack, programming language, databases, automation tools and even SaaS tools, all are one way decisions, but writing those down as your tech strategy helps immensely and eventually results in better software. This can be called a “tech constitution” for your product engineering org, and in many sense, this shared understanding of an important early stage one way decision is your software architecture.

So how do we achieve this? Few of the ways we can employ are the following:

- Implement standardization across programming languages, databases, caching, communication, services, and code structures.

- Create a comprehensive checklist for quality checks before production deployment.

- Point 1 and 2, then enable us to create inter-team flexibility to move people and overall system understanding for stability, scalability and modularity.

- Establish a clear understanding of “what” to build and “how” to build and integrate it.

- Shift architecture from a notional concept to the central guiding principle for the organization.

- Facilitate smoother onboarding and contextual understanding for newcomers. Automate a lot of day one tasks

- Reduce dependency on individuals for architecture decisions, freeing up bandwidth for more critical tasks.

- Apply convention over configuration

- And finally make testing first class citizen of your software development life cycle process.

As Group CTO in my previous organization, I was confronted with a cacophony of disparate tech stacks, where Java mingled with Scala, and Python danced with JavaScript, each marching to the beat of its own drum, with no coherent structure or semblance of inter-service communication. This was our Gordian knot, our architecture disaster.

The solution? We began by establishing a common language, a shared understanding that resonated across the organization. The Babel of languages was narrowed down to a standardized set, with similar curtailment applied to our database choices, all neatly packaged within a templatised code structure. The capstone of this transformative journey was a meticulously crafted checklist, delineating the mandatory quality checks prior to any code gracing the realms of production. This recalibration of our architecture compass did not just serve as a beacon for identifying and amending issues; it acted as a universal adapter, allowing our engineers to seamlessly interchange between teams, thereby optimizing not just for time, but also for the stability of our digital ecosystem.

This was not just an overhaul; it was a renaissance of our architectural philosophy. Gone were the days where the onus of understanding the ‘what’ and the ‘how’ of building and integrating rested on individual shoulders. Instead, a communal tapestry of knowledge was woven, where every thread contributed to a panoramic view of our architectural landscape. This newfound clarity not only became the nucleus around which everything else orbited but also became the bedrock that eliminated the need for constant contextual communication. Newcomers were no longer pilgrims in an unfamiliar land; they were now armed with a compass that pointed directly to the ‘why’ behind our actions.

This democratization of knowledge served as the linchpin that unshackled our bandwidth, allowing us to divert our focus from the mundane to the monumental. In the grand tapestry of our software architecture, each thread was now a testament to our collective wisdom, our shared vision, and our unified march towards a future defined by innovation, stability, and a harmonious symphony of technology.

The simplest reason, architecture like this excels, is that it allows product engineering teams to propel forward, and grows with them, thus removing the friction among the teams. Because everyone knows what to do and how to do it. That’s the purpose civil architecture serves. Isn’t it?

But software architecture goes without big upfront design, instead having a common understanding of the ability to explain to anyone by everyone that tells that “not only what to build but as well as how to build and integrate effectively and efficiently”